Can’t get enough of Pinterest for teaching? We can’t! We love looking for new pins related to close reading. Here are some of our faves!

Tag Archives: charts

Digital Reader’s Notebooks

Do you hate loose pieces of paper? Are your students’ reading logs floating in folders or getting lost in back packs? Do you love your students’ reading journals but worry about them being disorganized and chaotic? Do you have multiple organizational systems going all at once for organizing student book clubs? Digital Reader’s Notebooks can help solve these problems.

Do you hate loose pieces of paper? Are your students’ reading logs floating in folders or getting lost in back packs? Do you love your students’ reading journals but worry about them being disorganized and chaotic? Do you have multiple organizational systems going all at once for organizing student book clubs? Digital Reader’s Notebooks can help solve these problems.

Reader’s Notebooks are one of the most important components of the reading workshop. I LOVE using reader’s notebooks with my students because they house:

1) Reading responses, reflections, and musings

2) Notes from class, charts, graphic organizers

3) Drawings/ Illustrations

4) Jots, annotations, favorite quotes, text evidence

5) Book Lists

I would NEVER abandon the physical, paper reader’s notebooks, however, I use GoogleDocs in addition to the paper notebooks to create Digital Reader’s Notebooks with my fifth grade students.

Digital Reader’s Notebooks allow students and teachers to organize the materials that students use during the reading workshop. In the image above, you can see that my students have GoogleDoc folders for each subject area. Inside their reader’s notebook they have:

1) Reading Logs and Book Lists (Titles they have read)

2) A folder filled with images of class charts, flipped classroom videos, etc.

3) Digital Bins (Digital Text Sets)

4) Digital Reading Notebook (Shared Documents, Group Annotating, Blogging)

5) A folder for their book clubs

Digital reader’s notebooks allow students to stay organized. They are an invaluable resource in the reader’s workshop! Let us know if you use them or try using them. Also, if you have any questions, please post them below. We’re happy to share how we’ve used them!

The Argument Essay

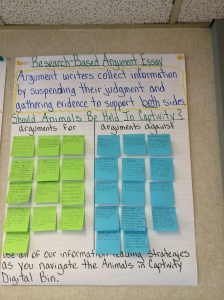

My sixth- grade students are finishing up their argument essays this week. I have found the strategies an d suggestions in The Research-Based Argument (Lucy Calkins, Mary Ehrenworth, and Annie Taranto) and by TCRWP invaluable.

d suggestions in The Research-Based Argument (Lucy Calkins, Mary Ehrenworth, and Annie Taranto) and by TCRWP invaluable.

In the past I’ve allowed my students to select individual arguments. I’m sure I’m not alone. I’m sure I’m not the only one who tried desperately to juggle 20 to 25 different topics and issues and provide feedback and support of great substance to each student. It’s an impossible task.

This year, my class chose one topic: Should animals be held in captivity. My students are doing some of the best writing I’ve seen in all of my years of teaching. Here’s why. Having one topic enables all students to engage in  conversations about an issue where they each can contribute. Have you ever had to peer-review a paper and struggled because you just didn’t feel knowledgeable about the topic? Sure, you’re able to provide feedback around the basics of writing: clarity, organization, style, mechanics. But when you know the topic well, there’s just so much more you can offer.

conversations about an issue where they each can contribute. Have you ever had to peer-review a paper and struggled because you just didn’t feel knowledgeable about the topic? Sure, you’re able to provide feedback around the basics of writing: clarity, organization, style, mechanics. But when you know the topic well, there’s just so much more you can offer.

Together, we created a digital bin that contains interviews, videos, and articles about the topic animals in captivity. Although students are working with the same topic, they are each able to research individually by selecting the texts they want to read from the digital bin. Using graphic organizers as they navigate each text, students take notes on the different perspectives the texts provide and they collect researchable evidence that supports each perspective. Each day, students work in small groups to discuss the research they’ve read. Then they write researchable facts on sticky notes that give reasons for or against the issue.

Here’s a chart I created for my classroom, inspired by a similar ch art in The Research-Based Argument. This is such a helpful chart for all students, particular my novice readers and writers. As they continue to navigate the digital bins and research this topic, we are reminded that this is a complex issue and we discuss the importance of suspending judgment in order to glean as much information as we can from our resources.

art in The Research-Based Argument. This is such a helpful chart for all students, particular my novice readers and writers. As they continue to navigate the digital bins and research this topic, we are reminded that this is a complex issue and we discuss the importance of suspending judgment in order to glean as much information as we can from our resources.

This process provides a momentum and energy that I haven’t seen previously. As they finish up their essays this week and share their writing, students are able to get feedback from peers who know their topic well and can offer precise and sound advice to help make the writing stronger. Although the issue is the same, each student’s approach to constructing their research-based argument is different. And I’m able to support each of my students because we’re all immersed in common texts and steeped in a common knowledge

On Teaching Interpretation

I want my students to be able to think for themselves. This is my teaching goal everyday. Teaching interpretation in a way that enables my students to think for themselves has been something that I’ve thought a lot about for the past decade.

It began ten years ago when I was teaching fourth grade. We were reading the book Tuck Everlasting. As a whole class, we were noticing Natalie Babbitt’s use of time: sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight. I had created an assignment for my students- “Note each event that is associated with a time period.” We were analyzing the connection between the mood & intensity of the event and the time of day when it occurred.

I will never forget one of my students asking me, “Ms. Johansen, if you hadn’t told me to look for this, how would I know?” At first, I laughed inwardly- such an astute question from a fourth grader. But then, I was fearful. I didn’t know how to answer. So I answered sternly and quickly, “This is why you have teachers. They will tell you what to look for.” This was one of my teaching-cringe moments. The moment when you know you are giving a terrible answer. My student wanted to be independent. She was looking for a strategy to notice the author’s use of mood, time, and symbolism. She wanted to learn how to think for herself. Above all, she was excited to learn how to notice hidden gems in a text and make her own interpretations. I let her down that day. And I’ve always remembered it.

At the time, I didn’t know how to answer her. I didn’t know which strategies to teach or even that there were strategies that could help her. I was simply making assignments and expecting my students to follow my directions. Now I know differently. I LOVE teaching strategies to students. I cannot imagine teaching any other way. Students need strategies to make the implicit, explicit, and the abstract, concrete. They can do this hard, thinking work on their own.

Redoes are vital. Since my student asked me that question ten years ago, I’ve had a dozen or so redoes. Now when students ask that question, I answer, “That’s a great question! I’m so happy that you want to uncover parts of a text that may seem hidden, on your own! Let’s talk about the strategies you can use and which elements you can be on the lookout for. I bet you’ll find many hidden gems on your own!”

Teaching strategies for helping students think about an author’s use of time and mood:

- Use the clip “Decision” from Disney’s Mulan (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zC2LGK9BdjU&feature=related) to discuss the time of day, light and dark, and weather used by the animators to create the mood of the scene. “Just like these animators, authors use the time of day to create the mood of the scene. It is important to notice the time of day in a story. It may be important and help you feel the mood of the scene.”

- Have students think about their own daily schedules. What moods do they associate with different times of the day? What activities take place at different times? How does light and darkness affect their moods and activities during the day. Why might this be important in texts as well?

- Use a text like Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt to keep track of the author’s use of time (sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight) and the mood of the event. Creating a chart or using a graphic organizer is best for this lesson. Students may notice that moments of revelation happen at sunrise, whereas, moments of intense action and emotions happen at midnight. (It is also good to notice the colors associated with these time periods. They may be symbolic.)

- Most importantly: Create a classroom chart that lists the many ideas students may want to be on the lookout for in a text. “Time of Day” should be on that chart.